Cycling From Beijing to Shenzhen |

Photographer's Notes on National Highway 107

Yang Fei

Changsha, China

A, Overview of the National Highway 107 Photography Project

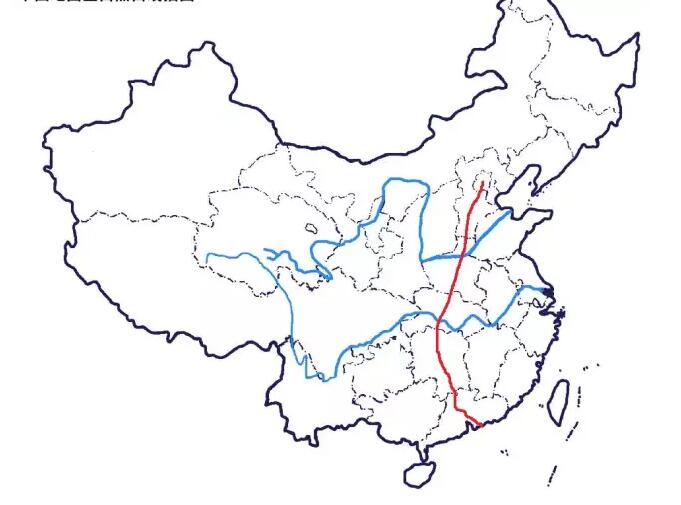

National Highway 107 (G107) stretches from Guang'an gate in Beijing in the north and ends at Wen'jindu land port in Shenzhen in the south, connecting six provinces and regions: Beijing, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Hunan and Guangdong. It has a total length of approximately 2,700 kilometers. Before the 1990s, there were only a few expressways in mainland China, and G107, running from north to south, was the most important highway in the country, bar none, with strategic significance similar to that of the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway.

On this map of China, the blue represents the Yellow River (upper) and the Yangtze River (lower), while the red line indicates National Highway 107 from Beijing to Shenzhen.

G107 is possibly the oldest highways in China. Its predecessor was the Jinghan (Beijing-Wuhan) and Yuehan (Guangzhou-Wuhan) highways, of which the Changsha to Xiangtan section (Changtan Highway), built in 1913, was the earliest dedicated road for automobiles in China. It was initiated by Tan Yankai, the then governor of Hunan Province. The man's vision was amazingly ahead of its time, as there were very few automobiles in the whole of China in 1913. If Liu Zhijun, Minister of Railways,faced great pressure overseeing the construction of China's high-speed rail system in 2008, then Governor Tan Yankai, who advocated for the construction of the Changtan Highway in 1913, truly faced enormous challenges.

On November 14, 2008, I embarked on a solo bicycle journey along G107 starting from Beijing. Passing through Shijiazhuang, Zhengzhou, and Wuhan, I traveled a total of 1,750 kilometers in 19 days and arrived at my home in Changsha on the evening of December 2nd. After a pause of over two years, on March 28, 2011, I set off again from Changsha, passing through Hengyang in Hunan and Lianzhou in Guangdong, and finally reaching Shenzhen. This segment covered a distance of one thousand kilometers and took me 14 days to complete. With this, my entire National Highway 107 journey came to an end, totaling 33 days and covering a distance of 2,750 kilometers. I captured over 8,000 photographs along the way.

Cycling on G107, you can often see the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway running parallel to G107. The white train is the CRH Harmony high-speed train. Image ID: R0014943.

B, Why Shoot National Highway 107?

Roads help us move fast. Generally speaking, when we are on the road, it is to go somewhere, and the road itself is not important. However, there are also some people who like the feeling of being on the road, who like the road itself, and it is not important where it leads. Being on the road means no longer adhering to the 9-to-5 routine. It represents rebellion and a disdain for conventions. Being on the road also means embracing uncertainty; you never know what will pop up on the road the next minute.

As far as documentary photography is concerned, special scenes such as war, riots, impoverished villages, and madhouses have long been the main characters. However, I have always believed that recording the daily lives of ordinary people, their clothing, food, housing, and transportation, is more representative of life as a whole. It is not advisable to excessively document madhouses, to avoid giving others the impression that China is filled with madmen. My home is in Changsha, and G107 passes by year after year. However, I have never seen anyone systematically document this highway. This road traverses provinces and counties, encompassing both urban and rural areas, making it excellent material for humanistic documentary photography.

Three major religions huddled together, with a chapel on the left, a King Guan Hall (a Taoist temple) on the right, and a Buddha statuette shop in the centre. The chapel was obviously converted from an ordinary residential house. Three kids ran by with laughter, and I quickly pressed the shutter. Leiyang, Hunan, March 2011. Image ID: Alim1470.

Many predecessors enjoyed wandering along roads. The iconic figure is Jack Kerouac, author of "On the Road," a classic work of the "Beat Generation" in the 1950s. Swiss photographer Robert Frank also traveled across the United States by car and later published the photo book "The Americans" (1958). To be honest, some of the photos in this book are out of focus, and some have crooked horizons, but it doesn't detract from "The Americans" being a modern artistic classic. In China, Luo Dan's "National Road 318" series completed in 2006 also won the gold award at an international photography festival. Of course, not everyone in this world is a lover of wanderlust; some people naturally dislike traveling. I belong to the middle ground, generally staying at home and occasionally traveling far away. If you want to go out and record life, you can't do better than to shoot along a road.

C, Transformation of a Pawn

In mid-November 2008, I was focused on shooting a Beijing-themed project, mainly consisting of scenic and eye candy photos, with the intention to sell them to travel magazines and photo agencies. In theory, I was also one of the promoters for the tourism industry. Not only did I provide ammunition for the industry, but I also provided technical guidance. At that time, I was about to submit the manuscript of the book "Travel Photography Quick Guide in Digital Era" to the People's Posts and Telecommunications Press.

In 2008, global climate change was becoming a hot topic, and the tourism industry was also booming. It's a green business that doesn't produce smoke or consume fossil fuel, and brings in big bucks. But the question is: can tourism be sustained without airplanes, cars, airports, hotels, and highways? Undoubtedly, from a systemic perspective, the tourism industry relied heavily on heavy industries and wasn't that green. So, on that autumn night in Beijing, I suddenly didn't want to be a pawn for the tourism industry anymore and decided to leave Beijing and go home.

Shanghai is the starting point of National Highway 312. This photo of Shanghai Huangpu River was one of the eye sugar scenes I captured, and it has been used on book covers and in geographical magazines, helping me earn a good amount of money. However, making money is not the original purpose of photography.

Geography and travel magazines are often dominated by praise and rarely negative narratives. The Chinese National Geographic has even released an album calling the National Highway 318 China's scenic route, with magnificent scenery and simple people. I don't deny this, but when discussing something, we should consider both the good and the bad. There is no purely positive thing in this world. After riding down G107, I feel that China's mountains and rivers are magnificent but polluted, and the people are simple but many of them are living a difficult life.

If I quit photography, what else could I do? When the future in limbo, I decided to subject myself to self-torture to see if it would help. Nietzsche said that great pain is the last liberator of the spirit, and only this kind of pain makes one enlightened. So I set out to ride G107 alone. This was my way home.

I basically didn't visit any tourist attractions during the 33-day bicycle journey, with the exception of the inexpensive Lugou Bridge by the road side. I have always been averse to non-natural attractions with entrance fees exceeding 60 Yuan. The ticket price for the Forbidden City is only 60 Yuan, while some relatively unknown so-called attractions have ticket prices much higher than that. This logic is difficult to understand. Given the current situation, tourism development in many parts of China has become a kind of imperialistic behavior, where developers grab the spots and aim to quickly maximize profits. China's per capita income is not high, yet the ticket prices of tourist spots is one of the highest in the world, and I don't want to support this predatory profiteering behavior.

If I could only choose one photo for this 107 National Highway album, then it would be this one. It reflects the resilience of ordinary people amidst the expansion of heavy industry and environmental pollution. Chenzhou, Hunan, April 2011. Photo ID: R0045387.

D, Why Ride a Bicycle?

As a deep green environmentalist, I won't use any wheels if I can walk, and I won't use four wheels if I can manage on two. Riding a bicycle for thousands of miles home makes it easier to take more pictures, and it also shows your green attitude.

Low-carbon and environmental protection should not just be empty words; we should start from ourselves and small things. Some people talk about environmental protection every day, but in reality, they live in luxurious villas and drive high-emission cars. They are the so-called pseudo-environmentalists. The former Vice President of the United States, Albert Gore, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his global publicity on the greenhouse effect, but his luxurious residence has more than 20 rooms and a private heated swimming pool. In order to show that he is an environmentalist, he has covered the roofs of all his rooms with solar panels. Should we learn from him?

Construction worker. Shenzhen, April 2011. Image number: R0048424.

The ride on the G107 covered 2800 kilometers in 33 days, an average of 85 kilometers a day. That speed is almost a joke by cyclist standard, and 150 kilometers a day is common for many of them. However, I am not a pure cycling enthusiast. Cycling the G107 is mainly for photo taking, and the bicycle is just a means of transportation for photography. I have a strong interest in documenting daily lives of ordinary people, capturing anything with text along the roadside such as slogans, road signs, menus, notices, and announcements, regardless of how insignificant they may seem. This approach requires frequent stops to take photos and it is not feasible to ride fast.

If you want to capture a road, the number of photos taken is generally inversely proportional to the speed of travel. The high-speed train is the fastest, but you won't be able to capture much. To capture the things on both sides of the road in the United States, you would have to walk to New York. Walking from Beijing to Hong Kong along the G107 would take two to three months, which is too time-consuming. A bike would do it in a month and help me lose weight. Of course, a motorcycle is even faster, but riding motorcycles is not allowed for ordinary people in the major cities along the way (the ban on motorcycles is one of China's characteristics), which confuses me. Walking is too slow, motorcycles are not allowed, and cars move too fast to capture anything meaningful, so cycling is the only option.

I had already rushed through this big downhill, when I suddenly noticed two elderly people by the roadside. I braked sharply,turned around, and asked if I could take a picture. The old man nodded with a smile. Xinyang, Henan Province, November 2008. Photo No. R0017092.

A desolate provincial border. It's 2,050 kilometers from Beijing, according to the road signs. Yizhang County, Chenzhou, Hunan, April 2011. Image number: R0045844.

E, the Significance of Time and Photo

According to the information I found, the pinyin alphabetic numbering of highways in China started in 1988 when the Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC) issued the "Rules for Naming, Numbering and Coding of Highway Routes" (GB917.1-88), with X standing for county highway, S standing for provincial highway, and G standing for national highway and expressway. The numbering of highways in China prior to 1988 has yet to be confirmed. I have photographed an old milestone on G107 engraved with the words "Line 107", which must be from before the 1980's. Many of these old mliestones have been destroyed, and some are half-buried, showing the traces of time and the never-ending process of highway renovation and heightening.

This half buried road milestone must be from before 1980's. Qingxin County, Guangdong Province. R0047124

I like to emphasize the value of time. Anything that cannot withstand the test of time is generally not worth the effort. With the interconnection of expressways, ordinary highways are becoming increasingly deserted. Many restaurants and gas stations along National Highway 107 have been abandoned, covered in rust and overgrown with weeds. The sound of the wind blowing through the broken iron sheets makes me feel disoriented. Will these roads continue to exist in the long run?

Someone once asked, what is the point of filming a road endlessly? Well, there may not be a correct answer to this question. If we keep asking this way, nothing makes sense. What is born must die, just like life itself, which eventually perishes anyway. I can't think like this, I should emphasize the relative value of time. It seems that all good works have an implicit standard, which is that they must stand the test of time. But any photo, no matter how rubbish it may seem, will show its value after several decades. Any photo from the Republic of China era that has survived until now is considered a treasure. What is the significance of the criterion of standing the test of time?

My imagination: If someone had taken a set of photos along the roughly G107 during the Republic of China era, no matter how poorly they did, I would be very happy to use them for comparison and see the changes in the scenery and culture of the highway over several decades. Unfortunately, I have not found any similar works from predecessors. I hope that future generations can find the G107 scenes I documented in the database. In a sense, this G107 album is a first-hand material for sociological field investigations, and hopefully these footage will have some historical value after several decades.

As a former commercial photographer, I have always hesitated about whether or not to upload so many aesthetically unpleasing garbage photos. It would be a waste of readers' time and akin to slow murder. Having so many garbage photos also seriously undermines my photography reputation. However, in the end, I spared no effort and uploaded over four thousand photos on the website. Of course, the vast majority are mundane, to put it nicely, purely documentary. By doing so, I also wanted to reflect the arduous process of photographing the highway through a large number of factual images. Life is not all about selected album photos, life itself is mostly rubbish.

It is good for rubbish to be classified, and these over 4,000 pictures of G107 are classified into the following 27 categories:

1. 107 Images of G107

2. G107 Performance Art and Installation Art

3. Shocking Series

4. One City, one Image

5. National Highway People

6. National Highway Scenery

7. Architecture 1: Residential Buildings

8. Architecture 2: Non residential Buildings (urban)

9. Architecture 3: Non residential Buildings (rural)

10. Various foods

11. Street Documentary

12. Family Planning Series

13. Village Direct Elections

14. Slogans and Roadside Texts

15. Still life and Close-ups

16. Road Signs and Milestones

17. Gas Stations and Toll Booths

18. Various Vehicles

19. Notices and Announcements

20. Paths and Roads

21. Hotels and Rooms (including tents)

22. Environmental Conditions

23. Roadside Advertising

24. Gates

25. Images and Thoughts

26. Questions and Quizzes

27. Roadside Sculptures, Paintings, and Other Works

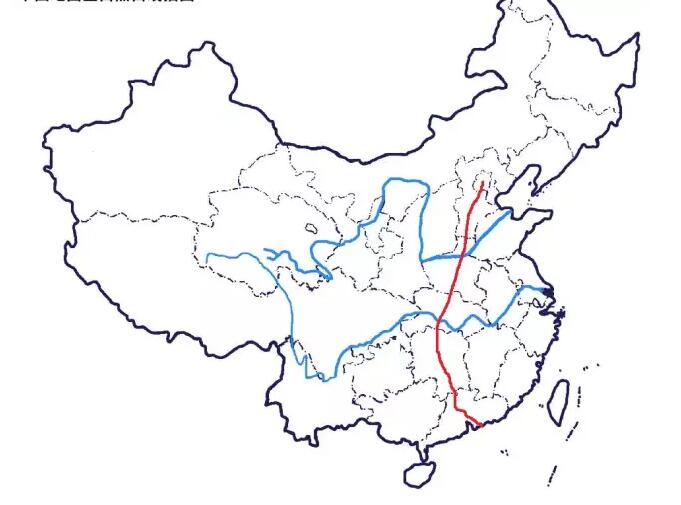

At the entrance of the city gate tunnel, portraits of Chairman Mao and Feng Shui objects are sold together. The walls of Dingzhou are genuine Ming Dynasty antiques, and this is a true ancient city with people living in it. In many places, residents are forcibly relocated, and ancient buildings are fenced off for tourists to see. Such ancient buildings have no vitality. November 2008 , Dingzhou, Hebei.

Photo categorizing photos is a challenging task. An object usually has multiple attributes. For example, a car can belong to both still life and transportation categories. Similarly, many portraits of individuals can also be classified as street documentary. There are many such contradictions. These categories are just rough classifications, sometimes based on intuition.

Among all the methods of categorizing photos, the simplest one is arranging them chronologically. This is essentially a photo diary, and many travel journals on social media and forums are presented in this way. I'm no exception. Due to the length limitation of this book, it is not feasible to arrange thousands of photos in chronological order. If you would like to read the cycling diary of G107, please click on the following table of contents:

The Chinese characters on the right read "Farewell Dad". Simple and plain, but it carries much more emotional impact than phrases like "eternal glory." Arriving at this point, I couldn't help but felt infinitely sad, as my father was also dying. Hengshan County, Hunan, March 2011. Photo ID: Alim1118.

F, Impressions of the National Highway

In simple terms, there are a few key points that left a deep impression on me during this journey along G107:

1. The residents along the G107 are becoming increasingly wealthy, with over 80% of rural households being newly built two or three-story brick and tile houses, and a few of them are even close to villas standard. It was challenging for me to find a typical traditional mud-brick house to photograph.

2, There are many homeless wanderers on the national highway. Almost every ten kilometers, you would come across one. Most of them appear dirty, with disheveled hair, rummaging through garbage piles for food.

An elderly person living in a roadside shack. Xianning, Hubei, November 2008. Photo ID: R0017870.

The environmental pollution along G107 is severe. On one hand, there is industrial pollution, with tall chimneys emitting billowing smoke visible everywhere. On the other hand, there is domestic waste. The national highway has been becoming a natural garbage dump for residents along the road (especially in urban fringe areas), with piles of garbage and stinking ditches stretching out in all directions. The most severe water pollution is found in the Pearl River Delta region, specifically Guangzhou-Dongguan-Shenzhen section. The rivers along the route are dark and filled with foul-smelling water, making me feel dizzy and nauseous. I have to cover my nose when crossing bridges. The residents of the Pearl River Delta seem to have very strong physical resistance, and this kind of water quality is unexpectedly safe and sound for them. Treating freshwater resources in such a way is truly worrying for the consequences it may bring.

It is puzzling that in Guangzhou and Dongguan, where the water quality is poor, eye-catching environmental protection slogans are everywhere in the streets, such as "Firmly Tackling Pollution" and "Scientific Water Management for the People", etc.

It is dangerous to capture scenes of pollution. In November 2008, in Neiqiu County, Hebei, I was ordered by local police to hand over my camera when I was capturing the billowing smoke from a steel mill. I repeatedly explained that I was there for tourism purposes. Finally, the police said, "Capture what you should capture and don't capture what you shouldn't, to avoid unnecessary trouble."

Major developed countries have bid farewell to the era of heavy industry, while China is rapidly becoming the world's factory and is entering a period of heavy industry with high capital construction. Therefore, China's pollution problem may continue to worsen in the next 20 years. It is worth pointing out that it is not the coal bosses and mine owners who want to pollute the environment on purpose. Pollution of the environment is closely related to the population's pursuit of heavy industrial products such as housing and automobiles. In other words, everyone is behind the pollution. As long as our desire for material goods is not controlled, the environmental awareness of enterprises is not raised, and the corrupt behavior of officials is not effectively stopped, it is very difficult to solve the problem of environmental pollution. I will discuss this issue in another article.

Banner signs are one of China's specialties. This lady used a banner to build a makeshift shelter, intending to do some roadside business. This scene reflects the indifference of the common people towards advertisements and propaganda, as well as their desire for survival. Luohe, Henan, November 2008. Image number: R0016871.

In the online version of the G107 album, I have summarized a number of performance art and installation artworks (some of which are environmental pollution scenes). These so-called artworks may be commonplace to local residents, but for comrades unfamiliar with the countryside and the urban fringes, these images may make them wonder: is this what's going on in China? Can these things be considered works of art?

In recent years, I have visited many contemporary art exhibitions in Beijing and Shanghai, including some famous works from the UK, but to be honest, I don't really understand them. In my understanding, contemporary art is about collecting things that seem inexplicable or absurd, and then putting them in art galleries. In my opinion, some scenes on the G107 are quite similar in nature to works of performance art and installation art. With a bit of packaging, they could be put in art galleries too. I'm going to do some packaging work through this topic.

Classical art has reached its pinnacle after thousands of years of development. Without breaking the rules, contemporary artists will live in the shadows of classical masters. From this perspective, the rise of contemporary art reflects the despair of today's artists. They cannot win the competition, so they change the rules of the game. Although I don't fully understand the contemporary artworks in galleries, their proclamation of "everything is art, everyone is an artist" resonates with me. I believe that on the G107 national highway, everyone is a natural artist, and everyone is a director of their own life. And isn’t cycling the G107 itself could be considered a form of performance art?

Children's strollers, adults' motorcycles, and ancestors' graves. Yizhang County, April 2011. Image number: R0045756

G. Cycling summary (cameras, vehicles, and road conditions, etc.)

The Canon 1DsII digital SLR, which I use for work, was left at my friend's house in Beijing. For the Beijing to Changsha section of the G107 riding, my main camera was the Ricoh GX100 pocket camera. From Changsha to Shenzhen, I didn't even use camera anymore. I mainly used my phone to take photos, the Huajing Altek806. It's a knock-off camera phone with a 3x optical zoom and 12-megapixel resolution. My conclusion is that smartphones are fully capable of capturing exhibition-quality photos. Nowadays, phone cameras have surpassed 10 million pixels, and they also support full HD video. This G107 album also demonstrates that everyone now has a handy creative tool, so there's no need to complain about cameras anymore.

My bike is a folding 20-inch small-wheel bicycle (Dahon SP16) with no modifications, just added a speedometer. The advantage of a folding bike is that it's convenient to take into hotel rooms. I have extremely minimal luggage, only a set of spare underwear (in Zhaoliqiao, Hubei, my jeans ripped in the crotch after thousands of miles of riding, and there were no pants available on the road, so I awkwardly wore open-crotch pants for a day). I wanted to test it out and see how far I could go on a small wheeled folding bike, and it would be great to ride all the way back to Changsha, but if I couldn't, I could just fold it up and get on a train and go.

Out with the old, in with the new. Hengyang, Hunan, March 2011. Photo No. Alim1223.

Food and water are nothing to worry about. There are kiosks in every village. On average, there's a village every 10 kilometers, a township every 20 kilometers, a county every 60 kilometers, a medium-sized city every 120 kilometers, and a major city (provincial capital) every 400 kilometers. Most of the townships have very poor hotel accommodation, and only the county towns have decent hotels. As for big cities, it goes without saying that you might not have enough money. Plan your trip well and try to get to the counties and cities before dark, otherwise you still need a small sleeping bag, because the hygiene of roadside inns in the townships is so suspicious that I don't dare to sleep with my clothes off.

G107 passes through dozens of counties, more than two dozen medium-sized cities, and six megacities, but it's not easy to get lost because there are milestones every kilometer. However, a well-performing compass is a necessity. From Beijing to Shijiazhuang, you basically follow a southwest direction. From Shijiazhuang, continue heading due south and stick to this general direction, and you won't go wrong. The only trouble I encountered was in Wuhan. This city is too big, and many streets are not oriented north-south or east-west. When asking for directions, three people might give you four different answers, and I was left bewildered. Most of the time, what the locals say is not wrong, as there are indeed multiple routes to a destination in a super-sized city like Wuhan. Because there were too many answers, I stopped asking for directions and bought a map of Wuhan. Using a compass, I successfully navigated my way out of Wuhan. I have GPS on my phone, but I have never used it along the way.

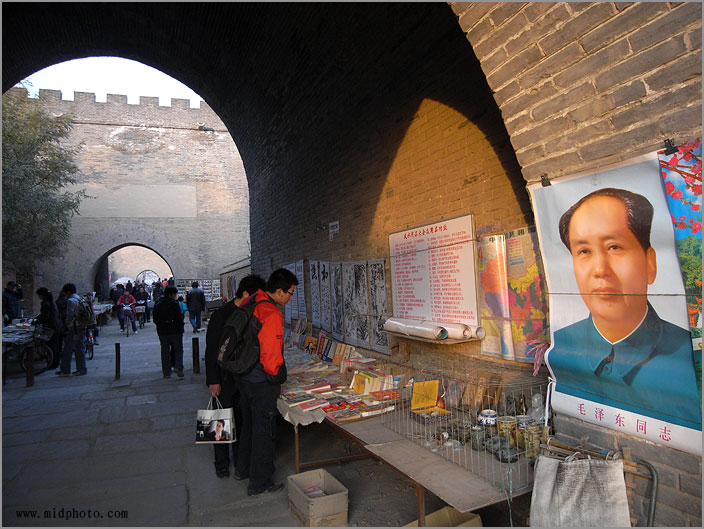

Endless loneliness. Hebi, Henan, November 21, 2008. Image number: R0016191.

During the 33 days on National Highway 107, I thoroughly enjoyed the solitude of being on my own. Apart from booking hotel rooms at the front desk and occasional inquiries for directions, I traveled alone every day from sunrise to sunset. There were joyous moments running under the sunshine and tree shadows during the day, as well as fearful moments of pedaling desperately alone in pitch-black darkness at night (with the nearest accommodation still far away when night fell). In Xinzheng, Henan, when a cold wave struck, I ran a high fever and lay alone in a small hotel, even having hallucinations of dying in a foreign land.

Village-level direct elections. Buqitun Village, Weihui City, Henan Province, November 2008. Photo No. R0016408

The National Highway 107 project was completed, but it wasn't a very pleasant bike journey. The biggest threat on the road was the trucks. The horns of small trucks were sharp and piercing, tearing at one's heart and lungs. The horns of those train like giant monsters, with dozens of wheels, were much gentler, similar to ship whistles, producing low-frequency sound waves that travel far. Although it didn't tear at my heart and lungs, it made me even more uneasy because when these giant monsters passed by, the whole earth would tremble. Don't be too happy once they passed by, because tailwinds created by these monsters are similar to tornadoes. Hold onto the handlebars tightly and be careful with the direction.

Long-term cycling on national highways carries a high risk of pneumoconiosis. Poorly maintained agricultural tricycles, diesel trucks, and coaches emit black smoke while passing by, accompanied by dangerous tailwinds and clouds of dust. Along the way, many farmers have the bad habit of burning fields, causing a thick haze that's suffocating. In the road repair and construction site section, dust is blowing and sand is everywhere, making masks indispensable.

Overall, the road conditions of G107 are good. The 30-kilometer stretch at the Henan-Hubei border (under the jurisdiction of Suizhou, Hubei) and from Lianzhou to Qingyuan in Guangdong have poorer road conditions. Most of the G107 are second-class highway, and a few are first-class highway with isolation belts in the middle. Dozens of kilometers near Zhengzhou, Henan, the G107 have been upgraded to enclosed expressways, with excellent road conditions for a comfortable ride. The 40-kilometer stretch before entering Guangzhou has also become an enclosed expressway, but bicycles are not allowed, so I had to detour on county roads. To be clear, national highway does not mean high grade highway. Many sections of the National Highway 219 (G219) from Xizang to Xinjiang are unpaved dirt roads, while the county roads in developed regions may also be wide two-way eight lane roads.

The quilt and peach blossoms complement each other. Location: Xiangtan, Hunan. Time: March 2011. Image number: Alim0839.

Most of the trucks carrying coal, sand, and stones on the national highway operate naked - not to mention a cover plates, many don't even have a piece of cloth covering them. They pass by with whistling smoke and leave sand and small stones all over the roadside, occasionally interspersed with broken glass. These pose the biggest threat to pedestrians and cyclists. For safety reasons, bicycles can only be ridden along the roadside. Sand is not too bad, but one must be cautious of gravel. When rushing downhill, your bicycle may be overturned by a larger gravel, which is very dangerous.

Of course, there are also sections of national highway 107 with few vehicles, lush green trees, clear blue skies, and a pleasant breeze at your feet. The best scenery can be found in the area around Yangshan County, Lianzhou, in the northern part of Guangdong. Overall, about 20% of the G107 can be enjoyed for cycling pleasure. Life is often full of disappointments, and this statement holds true.

Yang Fei,

Initial draft: January 2013,

Revised: June 2017

End of the photographer's note.

Click here to return to the G107 album

Follow Lao Yang at:

1, Yang Works: www.999kg.com

2, Telegram@feiyang17

3, Email:starrytibet@gmail.com

4, Medium@starrytibet

5, Twitter@feiyang17

6, Facebook@yangfei999999@hotmail.com